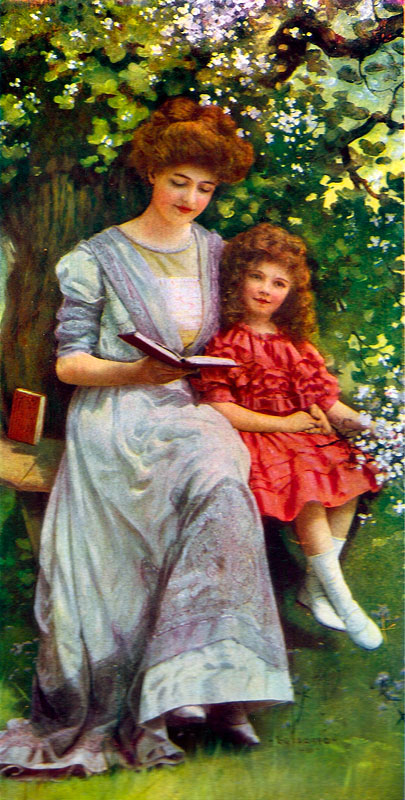

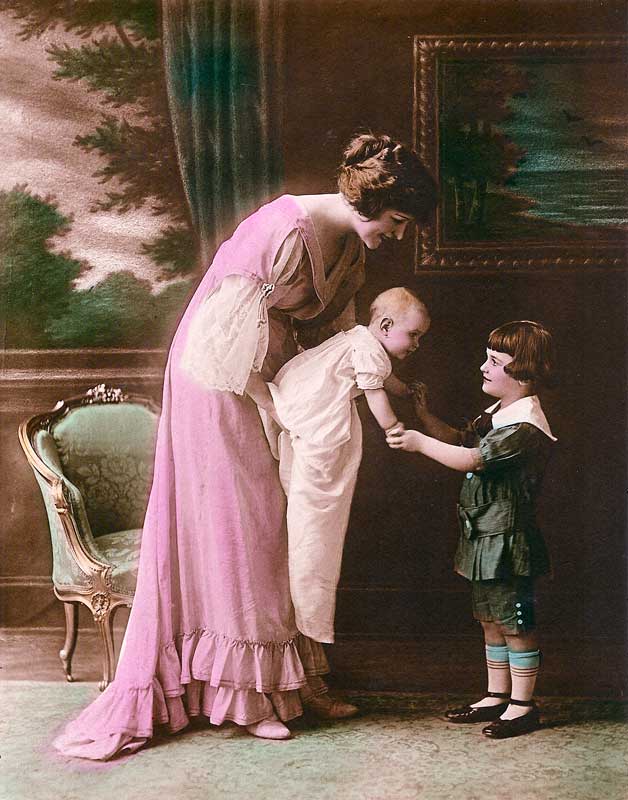

Two new additions to my Tonnesen collection, both original photos copyrighted by the Tonnesen sisters, feature notations that appear to be the handwriting of Beatrice Tonnesen. I’m showing the photographic images and the notations found on the back of each in the slideshow at right. You can compare the handwriting for yourself, by clicking on the link to “Beatrice Tonnesen’s Restored Scrapbook” near the bottom left of this page, and browsing through the many pages that contain dates and other information written by BT herself.

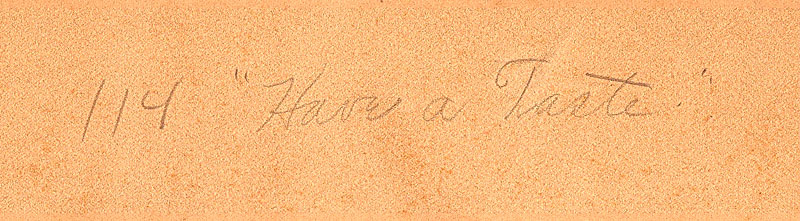

The first photo shown at right is titled “Have A Taste.” I purchased it from Christopher Wahren Fine Photographs of New Haven, CT. Mr. Wahren states that it is a “gelatin-silver print … perhaps with platinum admixture.” The word “print” in this context refers to a photo made from the original negative. The photos marked “Tonnesen Sisters” originated early in Beatrice Tonnesen’s career, before she used “T-numbers” – a capital “T” followed by a number – to identify her works chronologically. The few numbers I’ve found on other photos by Tonnesen Sisters have not appeared to be chronological. So I am unsure as to what the “114” found on “Have a Taste,” which was copyrighted in 1902, represents. The images marked “Tonnesen Sisters” were produced between approximately 1896 and 1903.

The second image showing the beautiful young girl holding bunnies in her apron, is a hand-colored photo. Brush strokes can be seen in some areas, and the lines on her blouse appear to have been added with a silver-tinged paint. There is no publisher listed, and it does not appear to ever have been part of a published calendar. So, believing it possible that it might have come directly from Tonnesen, I removed it from its frame and discovered the numbers “93” and “4” handwritten on the back. I could be wrong, but these look like Tonnesen’s handwriting to me. She is known to have been in the habit of making several photos for her own use from each negative at its time of creation. My guess would be that the “4” designates this as “Number 4” among those photos.

It’s exciting to find these little glimpses into the long-ago creation of these works of art! A good winter-time project for me might be to remove a few more of my treasures from their frames and see what hidden bits of information I might find.

Copyright 2012 Lois Emerson